A Soccer Game

(p. 78-80)

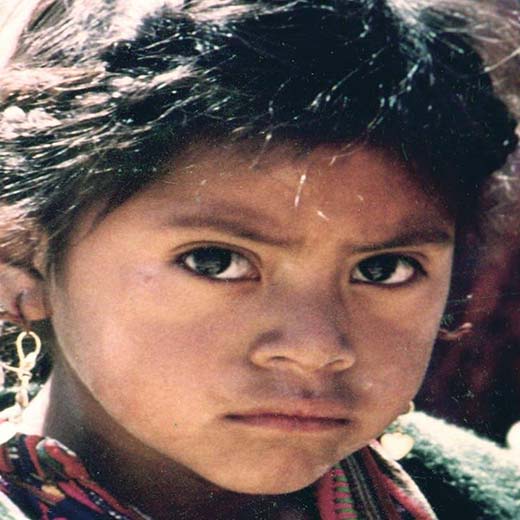

A few weeks later, as routine appeared to have taken over again in the region, people no longer talked about the passage of the military convoy or the ongoing strike in the banana plantations, no one wanting to raise the subject. But this apparent calm did not prevent Paul from worrying about his youngsters.

He wanted to take their minds off things, to distract them. It was with this in mind that Paul and Father Callaghan decided to invite the community youth to have a friendly game of soccer on a clear day. José agreed to grant leave to his students and referee the game since Father Callaghan had insisted on playing as a goalie. The latter also suggested that Paul do the same, to offer fair and equal chances for both sides, as he put it.

So, on that sunny afternoon, they were twenty youngsters plus the two goalies and one referee, gathered on the dirt road running along the western side of the village, not far from the cemetery. Jute bags filled with sand were used as soccer posts.

The fun began before the game started, when Paul protested that Father Callaghan had put on his priestly cassock to guard the goals.

“Father John, what's the idea of wearing a cassock?”

“To show on which side God will stand,” replied the priest, mockingly.

“It looks more like a sacrilegious act to me,” countered Paul.

“That's certainly not for you to judge,” added the priest to end the debate.

Everyone, except the priest, laughed heartily, then José called on the teams to play.

“That's enough now! Stop this childish talk and start the game!”

After Father Callaghan had stopped a few shots that should have passed between his legs, with his long cassock reaching down to his feet, Paul told José that he was considering filing a complaint of obvious cheating by the opposing goalie. The kids were having a great time.

At one point, Arnoldo, who was playing on Father Callaghan’s team, bluffed the opposing defense and suddenly found himself alone in front of Paul. Surprised by his own feint and probably too nervous to make the most of this unique opportunity, he rushed his shot and just missed the net guarded by Paul. The ball rolled about 50 feet until it disappeared into the ditch on the opposite side of the road from the village. Jorge, a defender on Paul's team, ran to get the ball, but stopped dead in his tracks when reaching the edge of the ditch, staring at the bottom, unable to speak. Alarmed by the boy's behavior, Paul rushed to join him. What he saw horrified him and left him speechless.

The ball had ended up on the belly of a mutilated body lying at the bottom of the ditch. Seeing their reactions, José turned to the other youngsters and told them to stay where they were; then he and Father Callaghan rapidly joined Paul to see the macabre scene for themselves. José gently took Jorge by his shoulders to draw him away from the scene. The boy burst into tears and buried his face in José’s shoulder. After a few words of comfort, José asked him to go join the other kids.

From where they stood, the three men could see that the body was disfigured. The skin had been removed from the face, probably to make identification more difficult. They were all in shock. Paul finally turned away from the scene and vomited. José went down to take a closer look. Father Callaghan made the Sign of the Cross and followed him. They both looked at each other, and their eyes spoke of a tacit understanding; they had identified who it was.

“He was tortured; some fingers are missing,” José said.

Father Callaghan began to pray for the repose of the deceased. José came out of the ditch and approached Paul.

Realizing that the latter had been sick, he asked, “Are you okay?”

Paul turned to him, looking dazed and confused, without saying a word. José reacted immediately by grabbing him by the elbow and adopting a stern tone.

“Come on, Paul! Pull yourself together! You have to take the kids back to the village.”

“But we can't leave the body like that,” Paul mumbled.

“I know. But for now, we must leave it there,” José replied, glancing at the wooded area at the top of the hill on his right. “Someone may be spying on us right now. I'll cover the body with leaves and brushwood.”

The priest, who just came up from the ditch and heard the last part, agreed.

“José is right. Nothing can be done now.”

“I'll come back with others during the night, and we'll take care of the body,” José added. Paul finally accepted and went to join the teenagers, who now knew what Jorge had discovered and were silently waiting.

José and Father Callaghan watched as the group moved off, then they went back down into the ditch.

“Did you recognize him?” the priest asked.

“It’s Eduardo. I saw him just before he left to make the rounds of his buyers. These are the clothes he was wearing.”

“That’s what I thought.”

“His wife must not see him like this.”

“I said the usual prayers. I know you will do the best under the circumstances.”

He took one last look at the mutilated body of Eduardo the saddler and left José, who began covering it with brush.

A Tribute to the Ancestors

(p. 135-136)

The next morning, two human silhouettes appeared in the dawn light on the path running through the same cornfield that Paul and José had taken to get to the pyramid. But this time it was José and the shaman Manuel going to the sacred cave under the pyramid to pay homage to the ancestors and ask for their protection for the newborn.

The shaman was leading the way. When they reached the fork where the main path continued uphill on their left up to the pyramid, they went straight on the small path that went down on their right and disappeared into the forest. A little further on, the trail became more and more rocky as it skirted the uncleared mound of about fifteen feet in diameter hiding most of the pyramid. Over time, shrubs and brush had grown on the grassy knoll and between large, mossy boulders littering the edge of the trail. During the whole trip, they remained silent, Manuel always keeping his eyes fixed on the way ahead, concentrated on the task at hand, while José seemed more feverish, listening for unusual sounds, rather rare in this stifling atmosphere. He was looking nervously around him, left and right, up and down, disturbed by the ambient dampness and the strange calmness of the place.

The trail ended at the cenote, the natural well adjoining the base of the great structure. The entrance to the cave, partially hidden behind the brush, seemed to go down under the pyramid. Once there, they took a short break to quench their thirst and mop up the sweat from their faces and necks.

Before entering the cave, the entrance to which corresponded to the size of a man of average height, Manuel took out some effects from a canvas bag embroidered with animal motifs, including a small clay pot with a chain, bits of pine wood, a bottle containing copal resin, and another one with pine resin. He put the pieces of wood and some pebbles collected in front of the cave entrance into the pot and then coated them with the resins.

José was carefully observing all of Manuel's actions. When these preparations were completed, the shaman turned to José to explain what he was doing.

“You see, these small pebbles are the guardians of this opening that gives access to the world of Xibalba, where our ancestors returned. By setting these stones on fire, I will awaken them and ask them to intercede for us with the spirits of the Underworld.”

José having nodded understandingly, Manuel lit the mixture he had prepared in the clay pot. Soon a thick black smoke rose, and the shaman started chanting a prayer while swinging his makeshift censer in front of the cave entrance.

“Oooo Xibalta, Oooo Tiox Mundo, Santo Mundo, forgive us for coming to disturb your sleep and I beg you, allow us to enter, me Manuel Ochte and my apprentice José De leon Ochte. Oooo Xibalta, Oooo Tiox Mundo, I beg you, grant us to meet the spirits of our ancestors to whom we ask for protection for José's newborn son.”

While continuing to swing his censer and mutter, Manuel slowly entered the cave. José followed, and soon the two disappeared, hidden by the column of black smoke coming out of the cave.

Massacre

(p. 246-248)

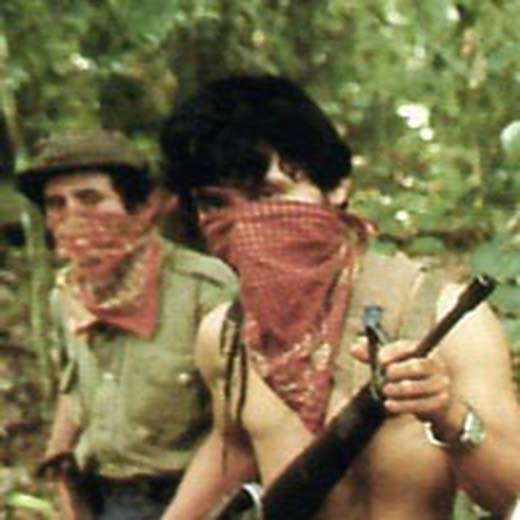

Early in the morning, during a patrol carried out at the beginning of May 1981, some 50 miles from their base camp, a group of twelve rebels, rifles slung over their shoulders, commanded by José, were moving silently on a trail through a small, wooded area on a hilltop, when Octavio, who was leading the way, stopped abruptly at the tree line, dropped to one knee and raised his right hand, ordering the group to halt. José, who was closing the march, hurried to join him at the edge of the woods, taking care to keep his body bent forward. Octavio did not even look at him; he just pointed down to a village nestled at the bottom of a small valley at the foot of the hill. Suspicious smoke was billowing from the center of the village. José took his binoculars and peered through them.

“The place looks deserted. The village has probably been raided.”

He scanned the village again, then the surrounding area, making a slow panoramic movement to the left and to the right on the hills that flanked it. The environment resembled that of Concepción, with several small plots of cultivated land on the slopes, crisscrossed by numerous paths and dotted with groves of trees.

After a while, he lowered his binoculars, and said, “Nothing, not a single person in sight.” He turned to Octavio and added, “Okay, I’ll go down to the village with three men. We’ll try to figure out what happened there. But first, you and the others will move discreetly on both sides of the village, staying under the cover of the trees on higher ground. As you go, try to find out where potential enemies might have come and gone. Once on the opposite hills, you will send light signals with a mirror to let us know if the way is clear. My group and I will then start to descend towards the village. You’ll do the same when you see us reaching the first houses.”

José and his group made it to the cemetery on the outskirts of the village without incident. There, they waited for a moment, crouching behind gravestones, listening to the slightest noise. Apart from the cawing of crows, nothing unusual. After a few minutes, José asked two of his men to thread their way between the houses along the ring road before entering the village and trying to make their way to the church. For their part, he and the other member of the group would take the side street leading to the cemetery from the main street to get to the central place. Then, weapons in hand, they set off, running from house to house, the cawing getting louder as they got closer to the public square.

Having reached the last building overlooking the public square, José poked his head out of the corner of the house to see if they could continue in the open. When he saw the macabre scene that those who had attacked the village had set up in the center of the square, his heart stopped for a second. The bodies of six naked men had been hung there on a makeshift frame, head down, hands and feet bound together. They had been severely beaten and emasculated. Numerous crows were feasting on pieces of flesh while several others swirled around the bodies. The advanced state of decomposition convinced José that the perpetrators of these atrocities had left the area some time ago.

They were finishing detaching the bodies when one of the men who had been sent to the church came running. Staring at the bodies lying on the ground with an expression of insanity in his eyes, he ended up saying in a breath, “What a bunch of barbarians!” Then looking up at José, he added in a strangled voice, “There are more... in the church.”

They rushed to the church where they found the other member of the group sitting on the porch steps. The scene he had seen inside had left him in a state of deep despondency. There were traces of vomit on the steps in front of him. He had no reaction when José passed by to enter the church. Although the smoke they had seen outside had cleared, a thick veil of ash dust still hung in the nave, and José had to wait a few seconds before he could make out anything in the dim light. As soon as he stepped inside, the smell of dead bodies became so unbearable that he had to cover his nose and mouth with a handkerchief. José then realized the full extent of the drama that had been played out in the village.

Most of the victims were women, children, and elderly people who, thinking they were taking refuge in the church, had instead found themselves trapped inside. Traces of explosives and burning odors indicated that incendiary hand grenades had been used. Those who were still alive were probably hacked to death with machetes. Wherever he looked in the nave, José could see dismembered bodies and suspicious splashes. It was indeed an act of genocide, the widespread massacre of a group of innocent Mayans Indians.

Infuriated, José stormed out, walked resolutely towards the petrified man still seated, grabbed him by the shoulders and ordered him to get up. Then he turned to the others, who looked overwhelmed and even discouraged. They needed to be shaken up.

“Okay, listen up!” he said. “This is no time to be downhearted. With Octavio and the others, we will track down those bastards to their lair and eliminate them before they strike again elsewhere. Then we'll come back here to properly bury the bodies of our brothers and sisters.”

Maya Sacred Calendar

(p. 271-273)

By late afternoon, the clandestine hospital was already filled with new patients, and half a dozen orderlies were moving back and forth between the house and the large tent. Sitting at the bedside of his son Arturo, resting in a cot a little apart from the others at one end of the veranda, José seemed to have regained his senses after having been reassured about his child’s state of health. The latter was sleeping soundly while his father was concentrating on drawing something in a small notebook with colored pencils.

Paul had just completed his third and final casualty transport. Mireya managed to intercept him as he was hurrying to his friend. She told him that José’s wife and mother had died during the attack on the rebel camp. Paul took a moment to digest the terrible news. He did not want to get too emotional when joining his friend. Still bending over his paper pad, José looked up when he heard footsteps approaching. He nodded toward his son with a rather pained smile, and said, “Mireya promised me a quick recovery with no after-effects.”

“It broke my heart when I heard about Anna and your mother,” Paul said, putting a friendly hand on José's shoulder.

“They attacked while most of the men had left the camp to go on patrol. When I returned with my group just before sunset, we found a scene of total devastation. Arturo was incredibly lucky. I found him under Anna...” Suddenly assailed by the memory, José stopped talking. His eyes misted up and he bit his lower lip to hold back his tears. Then, looking up at Paul, he cleared his throat to add with a tremulous voice, “At first I thought that he too was dead.”

She did everything she could to save him, and she succeeded,” Paul said, emphasizing Anna's courage. Then he asked, “What about Luis?”

“He probably managed to escape, or we would have found him,” José said, looking at Paul with a glint of hope in his eyes.

“That sounds very encouraging. But you haven't mentioned Manuel yet. Do you know what happened of him?”

José remained silent for a moment, his gaze lost in the distance, and then spoke with a firmer, deeper voice.

“Two weeks ago, while on patrol in the Totonicapan area, we came across a small, isolated village. The place seemed to have been deserted, but a plume of black smoke rising above the center of the village intrigued us. So, we decided to go and have a closer look at what it meant. When we arrived at the public square, we found six men hanged by their feet and emasculated. Most of the inhabitants had taken refuge in the church, probably believing that they were safe from violence because of its sacredness. (Then glancing at Paul with a look haunted by memory) The attackers barricaded them in and threw incendiary grenades through the windows. Those who survived the explosions were finished off with machetes...

… While those who left their villages to fight, the death squads are using scorched earth tactics. They raid villages to destroy crops and slaughter those who remained there, mostly women, children, and the elderly … When I told Manuel about what happened in Totonicapan, he decided to go back to Concepción, saying his place was there, among the elders. Before leaving, he also told me that he had taught me everything he knew and that it was now my duty to do the same with Arturo, so that he could become a leader and a shaman.”

“What will you do?”

“When Arturo gets better, I will take him to the Cuchumatanes and try to cross over to Mexico. I will do everything I can to ensure that he lives in a secure environment. I don’t want to stay here any longer. I think the military knew where to find us when they attacked our camp. The noose is tightening around us. You too should leave while you still can.”

“I can't just walk away and leave the injured. But if you think you've been betrayed or that someone has spoken under torture, you should raise those thoughts directly with Mireya,” Paul replied.

“So, I did. She said she would contact David to discuss it with him.”

Still uncomfortable with the idea of abandoning the injured, Paul wanted to lighten the mood.

“When I came to see you, I saw you doodling something.”

“I was drawing a calendar,” José said, showing it to Paul.

“Is this the one you call the Sacred Calendar?”

“Yes. We called it the Tzolk'in, which can be translated as the distribution of the days. That’s the one we use to determine the time of religious and ceremonial events. It is composed of two cycles, one of 20 named days associated with a picture or glyph with a distinct meaning, and one of 13 numbered days, each of which continuously repeats just like two-gear wheels with 20 and 13 teeth. It takes 260 days for the two cycles to realign on the beginning day of each cycle (260 = 20 x 13), so the Sacred Round has 260 days.”

Paul pointed to one of the symbols in the drawing.

“It looks like a frog.”

“Good point,” José said. “The frog is used to indicate when the waters are going to recede or when they have receded depending on the other symbols with which it is associated. There are different ways to interpret this statement. For example, according to Manuel, we are coming to the end of a long cycle of about 400 years, which would mark the transition from a period of great darkness to a new age of enlightenment and progress for the Mayas.”

José took out the page on which he had drawn the calendar.

“This one is for you, so you can practice deciphering it.”

“Wow, thanks José. I’ll treasure it.”

“It always does me good to draw the calendars. It allows me to situate what is happening in a wider context and reconsider our decisions accordingly.”

“Good point,” José said. “The frog is used to indicate when the waters are going to recede or when they have receded depending on the other symbols with which it is associated. There are different ways to interpret this statement. For example, according to Manuel, we are coming to the end of a long cycle of about 400 years, which would mark the transition from a period of great darkness to a new age of enlightenment and progress for the Mayas.”

José took out the page on which he had drawn the calendar.

“This one is for you, so you can practice deciphering it.”

“Wow, thanks José. I’ll treasure it.”

“It always does me good to draw the calendars. It allows me to situate what is happening in a wider context and reconsider our decisions accordingly.”